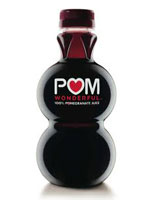

The makers of POM Wonderful pomegranate juice say that the drink improves blood flow and heart health, prevents and treats prostate cancer, and works 40% as well as Viagra (whatever that means). All for about four bucks a bottle.

Those impressive claims helped the company rack up $91 million in sales in 2009. They also earned the disapproval of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Last month, the agency sued POM Wonderful for making “false and unsubstantiated” health claims, and is asking the company to remove the claims from its ads.

A 100% juice drink that contains antioxidants (and no added sugar), POM is just one of many beverages that bill themselves as promoting better health. VitaminWater, kombucha tea, coconut water, and various brands of juice drinks made from acai, goji berry, and mangosteen have all used health claims in their marketing—and some, like POM, have been the subject of scrutiny and legal action.

The FTC, along with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has been cracking down on food and beverage makers for allegedly overselling the health benefits of their products. In 2009 alone, the FDA warned 17 companies that they were providing misleading nutritional information on their packaging or making overly specific health claims.

Not all of the products were drinks, but “the beverage category stands out,” says Bruce Silverglade, director of legal affairs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “At first blush it seems that beverage products are certainly a large proportion of food products that make bogus health-related claims.”

Drinks such as POM have become increasingly popular with consumers in recent years, thanks in part to public health campaigns against soda that have been prompted by the obesity epidemic. “The trend is away from traditional soda pop [toward] products claiming to provide magical health benefits,” Silverglade says.

Are the health claims true? Yes and no. The federal government doesn’t require companies to vet health claims with the agency before plastering them on product packaging (as long as the claims are accompanied by a disclaimer about their uncertainty). But that doesn’t mean the claims are invented—most are based in research.

The research is often funded by the manufacturers, however, and industry-funded research can be prone to bias. A 2007 study found that research on health drinks that was funded entirely by beverage companies was between four and eight times more likely to find a favorable result than research with no industry support.

“If a cell phone company told you they tested all the models and their model came out the best, would you believe it? Probably not,” says Lenard Lesser, MD, one of the co-authors of that study and a researcher at UCLA. “The same is true with nutrition research, but the stakes are higher because we’re putting our bodies at risk.”

Those impressive claims helped the company rack up $91 million in sales in 2009. They also earned the disapproval of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Last month, the agency sued POM Wonderful for making “false and unsubstantiated” health claims, and is asking the company to remove the claims from its ads.

A 100% juice drink that contains antioxidants (and no added sugar), POM is just one of many beverages that bill themselves as promoting better health. VitaminWater, kombucha tea, coconut water, and various brands of juice drinks made from acai, goji berry, and mangosteen have all used health claims in their marketing—and some, like POM, have been the subject of scrutiny and legal action.

The FTC, along with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has been cracking down on food and beverage makers for allegedly overselling the health benefits of their products. In 2009 alone, the FDA warned 17 companies that they were providing misleading nutritional information on their packaging or making overly specific health claims.

Not all of the products were drinks, but “the beverage category stands out,” says Bruce Silverglade, director of legal affairs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “At first blush it seems that beverage products are certainly a large proportion of food products that make bogus health-related claims.”

Drinks such as POM have become increasingly popular with consumers in recent years, thanks in part to public health campaigns against soda that have been prompted by the obesity epidemic. “The trend is away from traditional soda pop [toward] products claiming to provide magical health benefits,” Silverglade says.

Are the health claims true? Yes and no. The federal government doesn’t require companies to vet health claims with the agency before plastering them on product packaging (as long as the claims are accompanied by a disclaimer about their uncertainty). But that doesn’t mean the claims are invented—most are based in research.

The research is often funded by the manufacturers, however, and industry-funded research can be prone to bias. A 2007 study found that research on health drinks that was funded entirely by beverage companies was between four and eight times more likely to find a favorable result than research with no industry support.

“If a cell phone company told you they tested all the models and their model came out the best, would you believe it? Probably not,” says Lenard Lesser, MD, one of the co-authors of that study and a researcher at UCLA. “The same is true with nutrition research, but the stakes are higher because we’re putting our bodies at risk.”

11:27 AM

11:27 AM

ade nganthok

ade nganthok